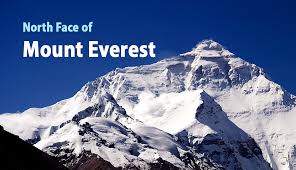

The North Face of Mount Everest isn’t just a slope—it’s a legendary test of human endurance. As the northern climbing route to the world’s highest peak (8,849m), this face has captivated adventurers for decades, blending extreme beauty with lethal danger. Whether you’re a budding mountaineer or an armchair explorer, this guide dives deep into the North Face’s geography, history, risks, and what makes it one of the most iconic routes on Earth. Let’s start by answering the most basic question: What exactly is the North Face of Mount Everest?

What Exactly Is the North Face of Mount Everest?

Defining the North Face: Location and Physical Features

The North Face of Mount Everest rises sharply above the Tibetan Plateau, in China’s Tibet Autonomous Region. Unlike the more famous South Face, which borders Nepal, the North Face is often called the “Tibetan Route” due to its proximity to the Rongbuk Glacier and the town of Lhasa.

Geographically, the North Face spans roughly 3,649 meters of vertical elevation from its base (North Base Camp at 5,200m) to the summit. Its terrain is a mix of steep ice couloirs, unstable rock bands, and avalanche-prone slopes. Key landmarks along the route include:

- North Base Camp: The starting point, nestled at 5,200m on the Rongbuk Glacier’s head.

- North Col (7,000m): A high-altitude saddle nicknamed “The Balcony of Death” for its brutal winds.

- Bottleneck (8,300m): A narrow, 50°-angled ice slope guarded by fixed ropes—often the crux of the climb.

- Summit Ridge: The final stretch to the top, where the South Face and North Face meet.

The face’s average slope angle is 35°, but sections like the Bottleneck climb to 55°, demanding advanced ice and rock climbing skills.

How the North Face Differs from Other Faces of Everest

Everest has four major faces, each with unique challenges. Here’s how the North Face compares:

| Face | Country | Key Terrain | Crowds | Sherpa Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Face | Tibet, China | Steep ice/rock, extreme cold | Low | Limited |

| South Face | Nepal | Khumbu Icefall (shifting ladders), Sherpa trails | Very High | Abundant |

| West Face | Nepal/Tibet | Technical rock bands, rare traffic | Moderate | Some |

| East Face | Nepal | Glacial complexity, minimal attempt | Extremely Low | Almost None |

The North Face’s lack of Sherpa support (compared to the South Face, where Sherpas carry supplies and guide) and steeper, colder terrain make it a less accessible route for beginners.

Why the North Face Matters: A Climber’s Gateway to the Summit

The North Face holds historical significance as the first route to Everest’s summit. In 1960, a Chinese team reached the top via this face, proving its viability. Today, it’s a popular alternative to the crowded South Face, offering solitude and a chance to follow in the footsteps of pioneering mountaineers. For many, summiting via the North Face is seen as a purer achievement—free from the “summit queues” that plague the South Face during peak season.

North Face vs. South Face: Why the North Is Infamous

Access and Starting Points

Reaching the North Face starts with a 4-day drive from Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, along a rugged road to North Base Camp. The South Face, by contrast, requires a 12-day trek from Nepal’s Lukla airport, ending at Base Camp (5,364m).

Permits are another key difference:

- North Face Permit: Costs ~$4,500 per climber (2024), issued by China’s Tibet Mountaineering Association. Requires a local guide (1:1 ratio for inexperienced climbers) and proof of high-altitude experience (e.g., summits on 6,000m+ peaks).

- South Face Permit: Costs ~$11,0000 per climber (2024), issued by Nepal’s Department of Tourism. Includes mandatory safety training and stricter altitude limits (e.g., no summiting above 8,400m without oxygen).

Climbing Difficulty: Technical vs. Physical Hurdles

The South Face’s Khumbu Icefall is infamous for shifting crevasses and falling seracs (ice towers). Climbers here tackle ladders and ropes through this chaotic zone. But the North Face’s challenges are more sustained:

- Yellow Band (6,800–7,000m): A 200m stretch of loose limestone and marble. Climbers must pick their way through unstable rock, often using crampons and ice axes despite the dry, rocky terrain.

- Bottleneck Couloir (8,200–8,500m): A narrow ice slope with 50°+ angles. Fixed ropes are critical here, but the couloir’s steepness and exposure to wind make it a high-risk section.

- North Col (7,000m): A saddle between Everest and Nuptse peak. Winds here average 150 km/h (93 mph), and temperatures plummet to -50°C (-58°F), earning it the grim nickname “The Balcony of Death.”

In short, the North Face demands technical precision (rock and ice skills), while the South Face focuses more on physical endurance (navigating the Icefall).

Weather and Seasonal Differences

Timing is everything. The North Face is typically climbed in spring (April–May) or occasionally winter (December–February). Spring offers stable winds and longer daylight hours (up to 14 hours), while winter brings sub-zero temps but fewer crowds.

Compare this to the South Face, which is almost exclusively climbed in spring. Its Icefall is dangerous in summer (daytime melting weakens ice) and autumn (unpredictable storms).

Temperature extremes on the North Face are brutal:

- Summit: Average -36°C (-33°F), with wind chill dropping to -70°C (-94°F).

- North Col: Nighttime lows of -50°C (-58°F), even in spring.

Reputation and Safety: Debunking the “Deadlier” Myth

Many think the North Face is deadlier than the South Face, but data tells a different story. From 2010–2023:

- South Face: ~300 fatalities (due to higher traffic).

- North Face: ~50 fatalities (fewer climbers, but higher risk per attempt).

The North Face’s fatality rate (deaths per climber) is actually slightly lower (1%) than the South Face’s (1.5%), thanks to stricter permit requirements weeding out inexperienced climbers. However, its reputation for danger persists: avalanches, falls, and oxygen failures are more common here, with rescue efforts often hindered by weather.

A History of the North Face: From Failed Attempts to Iconic Climbs

Early 20th Century: The First Reconnaissance Missions

The North Face’s allure began in the 1920s, when British expeditions first mapped Everest. Mountaineers like George Mallory (who famously said, “Because it’s there”) attempted the route but were stymied by freezing temperatures, lack of modern gear, and political barriers—Tibet was closed to foreigners until the 1950s.

By the 1950s, focus shifted to the South Face, where Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary summited in 1953. The North Face remained untouched until 1960.

1960: The Historic First Ascent via the North Face

On May 25, 1960, a Chinese team led by Wang Fuzhou, Qu Yinhua, and Liu Lianman achieved the first summit via the North Face. Their success was groundbreaking: they climbed without prior route-marking, relying on oxygen tanks and primitive ice screws.

Wang later recalled, “The North Face was a wall of ice and rock. We cut steps with pickaxes, our fingers numb, but we proved it could be done.” Despite initial skepticism (no photos were taken), the climb was later verified by Chinese authorities.

Notable Expeditions Since 1960

- 1984: Wanda Rutkiewicz, a Polish climber, became the first woman to summit via the North Face. Her journey, documented in The Ice Axis, highlighted the face’s technical demands.

- 1980: Reinhold Messner, an Italian mountaineer, completed the first solo winter ascent of the North Face. He climbed without oxygen, enduring -60°C (-76°F) temps—a feat still considered one of mountaineering’s greatest.

- 2023: Kuntal Kimri, an Indian climber, set a new speed record for the North Face, summiting in 16 hours (base to summit). He used lightweight gear and pre-placed oxygen to avoid delays.

Tragedies and Controversies

The North Face hasn’t been without loss. In 2017, an avalanche near the North Col killed 3 Sherpas. Two years later, a winter storm left 11 climbers dead, many caught on the face’s exposed slopes.

Commercialization has also sparked debate. Critics argue that guided teams with inexperienced climbers (some with minimal high-altitude experience) increase risks. As guide Tenzing Choden noted, “The North Face is tough, but the real danger comes from climbers rushing to the summit without proper acclimatization.”

The Geography and Geology of the North Face of Mount Everest

Rock, Ice, and Glaciers: The North Face’s Terrain

The North Face’s terrain is a mix of three elements:

- Rock: The lower slopes (5,200–6,400m) are limestone and marble, prone to erosion. The “Yellow Band” (6,800–7,000m) is a notorious section of crumbly rock, named for its pale hue.

- Ice: Above 7,000m, the face transitions to permanent ice. The Bottleneck Couloir (8,200–8,500m) is a steep ice slope, often compared to a frozen waterfall.

- Glaciers: The Rongbuk Glacier, which feeds the route, is critical for accessing Base Camp. But climate change has shrunk it by 1.5km since 1960, altering the approach path.

Adjacent Peaks and Landmarks

The North Face isn’t isolated—it’s surrounded by other giants:

- Nuptse (7,861m): A jagged peak connected to Everest via the North Ridge. Its ice cliffs drop into the Rongbuk Glacier, creating risky wind tunnels.

- Changtse (7,580m): Everest’s “sister peak,” located to the north. Its height funnels strong winds into the Bottleneck, making climbs here even more challenging.

- Lhotse (8,516m): The fourth-highest peak, linked to Everest via the South Col. While not part of the North Face, its proximity affects weather patterns.

How Geology Shapes Climbing Strategy

The face’s geology dictates every move. For example:

- Unstable Rock: The Yellow Band requires climbers to test each step—loose stones can trigger rockslides. Guides often advise climbing early in the morning when rocks are frozen and less likely to shift.

- Ice Seracs: Near the Bottleneck, towering ice structures (seracs) collapse without warning. Teams avoid these areas during windy days, relying on weather forecasts from Tibet’s Meteorological Agency.

Case in point: In 2019, a serac collapse in the Bottleneck killed a climber. Since then, guides enforce stricter timing for this section, only allowing ascents during calm weather windows.

Climbing Conditions on the North Face of Mount Everest

Seasonal Weather Patterns

Spring (April–May) is the prime season for the North Face. During these months:

- Winds drop to 100 km/h (62 mph) on average (from 150+ km/h in winter).

- Clear skies allow climbers to spot crevasses and seracs.

Winter climbs (December–February) are rare but possible. Conditions here are harsher:

- Temps average -50°C (-58°F), even during the day.

- Shorter daylight (8–10 hours) forcesTeams to climb in the dark, increasing fatigue.

Autumn (September–October) is emerging as a “shoulder season,” but storms roll in suddenly, making it risky. Only ~5% of climbers attempt the North Face then.

Temperature and Wind: The Harshest Realities

Wind is the North Face’s biggest enemy. During the 2023 spring season, gusts exceeding 180 km/h (112 mph) halted climbs for 5 days. At these speeds, even roped teams struggle to stand.

Temperature-wise, Base Camp sees overnight lows of 0°C (32°F), but at the North Col (7,000m), lows hit -50°C (-58°F). Frostbite can strike in minutes if gloves slip or boots crack.

Altitude Sickness and Oxygen Levels

Acclimatization is non-negotiable. Most climbers spend 4–6 weeks on the mountain, rotating between camps to let their bodies adapt. Here’s what happens:

- Mild Altitude Sickness: Headaches, nausea—1 in 5 climbers experience this.

- HAPE/HACE: Life-threatening conditions (pulmonary/cerebral edema) affecting 1 in 50. Symptoms include confusion, coughing up blood, or loss of coordination.

Supplemental oxygen is critical. Studies show 90% of North Face climbers use oxygen, with bottles costing $500 each. A typical climber needs 4–6 bottles to reach the summit.

Avalanche and Icefall Hazards

Avalanches are a constant threat. High-risk zones include:

- North Col Slopes: Wind piles snow into unstable slabs, which can collapse with minimal trigger.

- Bottleneck Couloir: Ice here is thin and prone to breaking, especially after daytime warming.

Safety protocols include:

- Daily crevasse checks by guides using ice screws and ropes.

- Weather alerts from Tibet’s mountain rescue team, which pause climbs during high avalanche risk.

Key Climbing Routes on the North Face of Mount Everest

The Standard North Ridge Route: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

Most climbers follow the standard route, which has five main camps. Let’s break it down:

- North Base Camp (5,200m):

The starting point. Climbers arrive after a 4-day drive from Lhasa and begin acclimatization with day hikes to 5,800m. - Camp 1 (6,400m):

Reached via the Rongbuk Glacier’s upper slopes. This is the first night at high altitude—climbers focus on sleeping with minimal movement to avoid altitude sickness. - Camp 2 (7,000m):

After ascending the “Yellow Band” (rocky section). Known for howling winds, tents here need heavy pegs and snow anchors to stay upright. - Camp 3 (7,800m):

The North Col. With winds up to 200 km/h (124 mph), this is one of the coldest nights on the route. Climbers rest briefly before their final push. - Camp 4 (8,300m):

The Bottleneck. Here, fixed ropes are essential. Climbers often spend 24 hours here, rationing oxygen and preparing mentally for the summit.

From Camp 4, the summit is just 500m away but takes 6–8 hours. The final stretch crosses the “Balcony” (8,400m) before the last ice slope to the top.

Alternative Routes: For Experienced Climbers Only

While the standard route is challenging, some tackle variations:

- North Face Direct: Avoids the Bottleneck, ascending a steeper ice line. Requires UIAA Grade 9 skill (extremely technical).

- Pinnacles Route: Climbs through sharp rock spires near the North Col. Rarely used due to rockfall risks.

- Winter Routes: Ascend without summer’s fixed ropes or Sherpa support. Only 1 in 10 winter attempts succeed.

Difficulty Ratings Explained

The North Face’s standard route is rated UIAA Grade 8 (extreme), meaning it demands advanced skills, specific gear, and high acclimatization. On the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS), sections like the Bottleneck ice slope rank Grade VI, while the Yellow Band’s rock climbing hits 5.8–5.9.

For context, UIAA Grade 8 is reserved for routes where “severe difficulties are anticipated, requiring extreme caution and specialized equipment.”

Navigation Aids: Fixed Ropes, Cairns, and Guides

Fixed ropes are the lifeline of the North Face. Over 2km of rope is strung between Camps 1–4, but these aren’t permanent—they’re re-set each season by Chinese guides.

Cairns (piles of rocks) mark the route, but heavy snow often buries them. Guides rely instead on memory, GPS, and weather patterns to navigate. As guide Ang Nyima noted, “The North Face changes yearly. You can’t trust old maps—you trust your eyes and experience.”

Safety and Risks on the North Face of Mount Everest

Common Accidents and Their Causes

The North Face’s most frequent accidents:

- Falls: Responsible for 60% of incidents. Icy steps and fatigue lead to slips, especially in the Bottleneck.

- Avalanches: 30% of accidents. Wind slabs at the North Col collapse easily, burying climbers.

- Oxygen Failures: 10% of incidents. Malfunctioning tanks or depleted oxygen force some to turn back.

Case study: In 2021, a climber’s oxygen tank failed at 8,500m. His guide shared their own tank, but both summited 2 hours late—exhausted but alive.

Rescue Challenges: Why Help Is Hard to Reach

Rescues on the North Face are rare and risky. Challenges include:

- Weather Windows: Storms can last days, delaying helicopter or ground rescues.

- Cost: A helicopter rescue costs ~$50,0000, often covered by expedition insurance (required to climb).

- Success Rates: Only 1 in 3 rescues are completed during critical moments.

In 2020, a climber with severe frostbite was rescued after 3 days. Five guides risked their lives to carry him down, highlighting the face’s unforgiving nature.

Regulatory Measures: Rules to Keep Climbers Safe

China enforces strict rules to reduce risk:

- Permit Requirements: Climbers must provide proof of summits on 2+ 6,0000m+ peaks (e.g., Denali, Aconcagua).

- Mandatory Guides: A local guide is required (1:1 ratio for first-timers).

- Waste Deposits: $4,000 deposit refunded only if climbers pack out 8kg of waste (including gear).

Pre-Climb Preparation: Fitness, Experience, and Mindset

To survive the North Face, preparation is everything:

- Physical Training: 6–12 months of cardio (hiking, cycling), strength (core, leg exercises), and cold tolerance (ice baths, winter hikes).

- Required Experience: Summits of peaks like Cho Oyu (8,188m) or Kangchenjunga (8,586m) are recommended.

- Mental Prep: Visualization, stress management, and accepting failure—only 60% of guided teams reach the summit.

Cultural and Environmental Stories of the North Face

Local Beliefs and Sacred Connections

To Tibetans, Everest is “Chomolungma,” the “Goddess Mother of the World.” Climbers often leave offerings—prayer flags, cairns, or small stones—at Base Camp as a sign of respect.

Sherpa communities, though based in Nepal, play a key role here. Many Sherpas guide on the North Face, blending their mountain traditions with local Tibetan culture.

Environmental Impact: Waste, Erosion, and Preservation

The North Face isn’t untouched by human activity:

- Waste: ~50 tons/year (vs. South Face’s 200 tons). Discarded oxygen tanks, torn tents, and food packaging litter the route.

- Erosion: Rongbuk Glacier’s retreat (20% smaller since 2000) has exposed unstable rock and ice, increasing avalanche risk.

China’s “Everest Cleanup” initiative (2023) now requires climbers to pack out 8kg of waste or lose their $4,000 deposit. Local teams like the “Everest North Face Clean Crew” remove 10 tons of debris annually.

Ethical Climbing: Balancing Adventure and Responsibility

Ethics on the North Face are debated. While some prioritize “summit at all costs,” others advocate for “climb with respect.”

As mountaineer and conservationist David Breashears put it, “Everest isn’t a trophy. It’s a sacred place. We must climb to honor it, not just to check a box.”

Key ethical practices:

- Pack out all waste (even small items like candy wrappers).

- Avoid disturbing wildlife (snow leopards and Himalayan monals live nearby).

- Never leave a teammate behind—group safety trumps individual ambition.

Planning Your North Face Expedition: Logistics and Costs

Cost Breakdown: From Permits to Oxygen

A North Face expedition isn’t cheap. Here’s a typical 2024 budget:

- Permit: $4,500 (China).

- Guide: $35,000–$55,000 (1:1 ratio).

- Oxygen: $500/bottle × 6 bottles = $3,000.

- Gear: $10,000+ (but rentable for $3,000).

- Miscellaneous: Meals, transport, insurance ($10,000+).

Total estimated cost: $50,000–$75,000.

Best Time to Climb: Aligning with Weather Windows

Spring (April–May) is optimal, with a 30-day window of stable winds and clear skies. Winter (December–February) is colder but quieter, with a 15-day window. Autumn (September–October) is possible but risky—storms often strike without warning.

Essential Gear List for the North Face

Don’t skimp on gear. Here’s what you need:

- Clothing: Base layers (merino wool), mid layers (fleece), outer layers (windproof/down parka rated for -70°C). Insulated gloves (rated -50°C), crampon-compatible boots.

- Climbing Gear: 12-point crampons, ice axe, carabiners (aluminum), harness, helmet.

- Tech: Satellite phone (InReach), GPS tracker, altimeter, cold-weather batteries (tested to -40°C).

- Medical: First-aid kit (bandages, painkillers), portable oxygen (2L/min), Diamox (altitude sickness medication).

Acclimatization Schedule: Preparing Your Body for Extreme Altitude

Acclimatization takes 4–6 weeks. Here’s a typical plan:

- Week 1: Arrive Lhasa (3,650m), drive to Base Camp. Day hikes to 5,800m to adjust to thin air.

- Week 2: Climb to Camp 1 (6,400m), return to Base Camp. Repeat to build red blood cell count.

- Week 3: Overnight at Camp 2 (7,000m). Day climb to 7,500m, return.

- Week 4: Overnight at Camp 3 (7,800m). Focus on rest—bodies struggle to recover here.

- Week 5: Final push to Camp 4 (8,300m), then summit.

Guides use the “climb high, sleep low” method: ascending to higher elevations during the day, then descending to lower camps to sleep, which accelerates acclimatization.

Interesting Facts and Records: The North Face’s Unique Milestones

Fastest Ascent via the North Face

In 2023, Indian climber Kuntal Kimri set a new speed record: 16 hours from Base Camp to summit. He used lightweight gear, pre-placed oxygen, and climbed nonstop, avoiding lengthy rest stops.

Oldest and Youngest Climbers to Summit via the North Face

- Oldest: 77-year-old Kami Rita Sherpa (2021), a veteran with 26 Everest summits.

- Youngest: 18-year-old Temba Tsheri Sherpa (2022), though age limits (18+) are strictly enforced to prevent underage risks.

Unconventional Attempts: Paragliding, Skiing, and More

- Paragliding: In 2019, French pilot Hugues Cabrière landed a paraglider from the summit to Base Camp, the first such feat on the North Face.

- Skiing: Norwegian climber Øyvind Lavardahl skied down the Bottleneck Couloir after summiting in 2020, requiring specialized cold-weather skis.

Seasonal Stats: How Many Climb the North Face Each Year?

- Annual Climbers: ~500 (vs. South Face’s 3,000).

- Success Rate: 60% (guided teams), 40% (solo).

- Fatalities: ~5/year (1% fatality rate).

What It’s Like to Climb the North Face: Firsthand Stories

Physical and Emotional Challenges: A Day in the Life

Sarah, a 2022 North Face climber, described her summit day: “We started at 6 AM, but by 8 PM, I felt like my legs were made of lead. Every step up the Bottleneck was agony—frostnip on my fingers, oxygen hissing in my mask. I wanted to quit, but then I saw the stars at 8,500m. That’s when I realized: this isn’t just a climb. It’s a journey.”

Breathtaking Views and Harsh Realities

From Camp 3 (7,800m), climbers see:

- Lhotse’s icy face to the south.

- Makalu, the fifth-highest peak, glowing pink at sunrise.

- The Tibetan Plateau stretching endlessly below, dotted with nomad tents.

But beauty comes with cost. Sarah added, “I saw discarded oxygen tanks and… human remains. Climbing isn’t just about reaching the top—it’s about respecting those who didn’t.”

Team Dynamics: Guides, Sherpas, and Fellow Climbers

Guides are lifelines. Chinese guide Ang Nyima (30+ summits) explained, “I’ve seen teams argue over rope fixes, but when the wind howls, you cling to each other. Trust is everything.”

Sherpas on the North Face often bond with climbers, sharing stories over heated tea in Base Camp. As one Sherpa said, “We’re not just guides—we’re your family up here.”

The Future of the North Face: Preservation and Innovation

Emerging Technologies for Safer Climbs

AI is changing the game. Tibet’s new AI weather model predicts wind patterns 72 hours in advance, helping teams avoid avalanche-prone days. Wearables like smart crampons (sensors detecting ice stability) and oxygen monitors (real-time flow alerts) are being tested to reduce risk.

Evolving Regulations to Reduce Risk

China is tightening rules:

- 2025 Proposal: Require proof of summits on 7,000m+ peaks (e.g., K2) to climb Everest’s North Face.

- Waste Policy Update: 10kg waste deposit (up from 8kg) to curb littering.

- Age Ban: Likely prohibit climbers under 20, citing physical/mental maturity risks.

Climate Change and Route Shifts

Glacial retreat is altering the North Face. A 2023 study by Tibet University found ice thickness in the Bottleneck has dropped 30% in a decade. Warmer winters mean softer ice, increasing crevasse risks.

Balancing Access and Preservation

Should the North Face remain open? Arguments:

- For Access: It’s a natural wonder—adventurers should have the chance to challenge themselves.

- Against: Commercialization harms the environment and puts unprepared climbers at risk.

Locals and climbers agree: “Preservation isn’t about closing the mountain. It’s about climbing with humility,” said Tenzing, a Base Camp operator.

Final Thoughts: Is the North Face of Mount Everest Right for You?

The North Face of Mount Everest isn’t for everyone. It demands experience (summits of 7,000m+ peaks), fitness (months of training), and mental grit (enduring isolation and fear). But for those ready, it offers unparalleled rewards: solitude, a piece of history, and the pride of conquering one of Earth’s toughest routes.

As Reinhold Messner, the North Face’s legendary solo climber, once said, “Mountains are not meant to be conquered. They are meant to be understood.”

If you’re still curious, check out our guides on high-altitude acclimatization or Everest climbing gear essentials . The North Face awaits—but only for those who respect it.

Featured Snippets:

- What is the North Face of Mount Everest?: The North Face is Everest’s northern climbing route, located in Tibet, China, known for steep terrain, extreme cold, and landmarks like North Base Camp and the Bottleneck Couloir.

- Is the North Face harder than the South Face?: Yes. The North Face has steeper ice/rock sections, less Sherpa support, and colder temps, though fatalities are lower per climber due to stricter permits.